If you work in consultation, engagement or public involvement, you’re probably aware of Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation.

Every project and plan that a government undertakes involves its citizens in some ways. In some areas, this means their voices are represented and changes are made accordingly. In others, unfortunately, performative citizen engagement can occur.

Arnstein’s Ladder breaks down the different ways in which governments can engage their citizens and local communities.

What is Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation?

Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation represents the different stages of citizen engagement in the decision-making process.

The lowest rungs represent decision making without really involving citizens, whereas the highest represent when citizen engagement becomes an important part of the decision-making process.

Arnstein’s Ladder was created to convey the importance of increasing citizen engagement and public participation so that every citizen feels involved in changes made in their community.

“The idea of citizen participation is a little like eating spinach: no one is against it in principle because it is good for you. Participation of the governed in their government is, in theory, the cornerstone of democracy—a revered idea that is vigorously applauded by virtually everyone.”

– Sherry R. Arnstein, “A Ladder of Citizen Participation,” Journal of the American Planning Association

The 8 Rungs of the Engagement Ladder

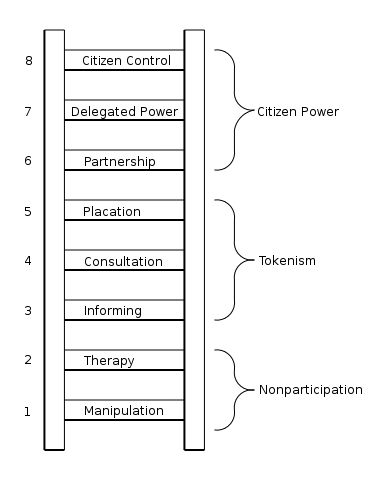

As shown in the diagram, Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation is split into 8 rungs and three sections. The lowest section is non-participation, followed by tokenism, and then citizen control.

Let’s break this down by rung to show how the different ways citizen engagement is used to give or even take away citizen’s power to influence the decision-making process.

Rung 1: Manipulation

The bottom rung of Arnstein’s Ladder is what she refers to as “illusory participation”. Rather than taking genuine stock in citizen’s input, they are placed in rubberstamp advisory committees or boards to educate them on why local plans are beneficial.

Rung 2: Therapy

Instead of involving citizens meaningfully, this rung of the Ladder of engagement refers to targeting citizens with group “therapy”, putting the onus of social issues on the community, rather than the government.

An example Arnstein uses in her essay is enforcing low-income tenants into schemes such as clean-up campaigns, rather than addressing wider issues in public housing programs that stakeholders are accountable for.

Rung 3: Informing

This is the first semi-legitimate step toward citizen participation on Arnstein’s Ladder. It involves actually “informing citizens of their rights, responsibilities and options.” However, what it fails to do is ensure the flow of information goes both ways, rather than just government officials to citizens with no reciprocal ability for the community members to share their views.

Rung 4: Consultation

The importance of statutory consultations for citizen engagement cannot be understated. Arnstein highlights the importance here however, of then actioning the information received. Without including other methods of participation during the consultation process, the input becomes a pointless information gathering exercise; or as Arnstein calls it a “window-dressing” exercise.

Rung 5: Placation

“Worthy” citizens are placed on advisory and planning boards, but have no real stakeholder power or say in the ultimate outcome. If it’s considered not legitimate or feasible by local powers, the citizen participation is still discarded as unimportant.

Rung 6: Partnership

Arnstein defines this rung of the Ladder of Participation as the redistribution of power. It’s arguably the first rung where citizen’s input is considered important by stakeholders and responsibilities and decisions in the planning process are shared.

This is achieved through joint policy boards, planning committees etc.

Rung 7: Delegated Power

This is when citizens can actually become the dominant decision-making authority over a particular plan. As Arnstein says, at this rung, “citizens hold significant cards to assure accountability of the program to them.”

They could manage community projects and key stakeholders will need to discuss and negotiate with citizens at length to achieve their goals.

Rung 8: Citizen Control

When citizens are in full control of a program, or project. This means everything from funding to policy to management and everything in between. On this final rung, citizens can negotiate the degree by which government officials etc. can alter the fundamentals or an organisation or project.

The Problem with Arnstein’s Ladder

Arnstein’s Ladder was developed in a time of systemic unfairness and exclusivity towards black communities of urban planning processes in cities in 1960s USA. It’s an attempt to identify what might be done to rectify this issue, so we get things like direct citizen control put forward as a defence against corruption or malicious political intent.

That means that its structure of citizen participation is very directly tailored to that era and the socio-economic and racial issues that were prominent in the 1960s.

Good involvement is about what’s appropriate to the decision at hand. And that needs a careful evaluation of each decision on its own merits. You can’t outsource that thinking to a single diagram.

There are loads of times and decisions where informing people is an absolutely essential part of effective participation – it’s not tokenism at all, or somehow a ‘lesser’ rung on the Ladder.

There are so many decisions where consultation is a formal, powerful, even legally recognised process for citizens to hold governments to account. And, while there are plenty of times where direct citizen control can be an amazing, appropriate and effective way to operate a decision-making process (things like thoughtfully-implemented participatory budgeting schemes, for example), there will equally be many times where actually it’s entirely the wrong way to involve people in the process.

Examples Of Good Practice in Citizen Engagement

Arnstein’s Participation Ladder implies that consultations remove citizen agency, but we disagree. Consultation is an essential part of the process, assuming the opinions shared are then taken on board in the planning process. In the UK, all consultations need to adhere to the four Gunning Principles to ensure they are fair and effective.

Good citizen engagement includes:

- Listening to public opinions and concerns

- Keeping residents and stakeholders informed at every step of the planning process

- Inclusivity: Ensuring all socio-economic groups and ethnicities are considered and heard during the process

- Transparent: Everything is readily available and in accessible language for all

Using Citizen Space, governments ensure that citizens get a real say in what happens within their communities.

Buckinghamshire County Council

When Buckinghamshire County Council wanted to set out new routes for pedestrians and cyclists, they used Delib’s Citizen Space platform for community engagement, consultation, and to hear their thoughts and concerns on the proposed 18-kilometre orbital park that would circle the town.

With a combination of community conversations, design sessions and online exhibitions, they were able to come up with a proposed route that bore the needs of the community members in mind.

London Borough of Southwark

London Borough of Southwark goes the extra mile in hearing its communities’ voices. They recognise that a statutory consultation closing, doesn’t mean the end of citizen participation.

Instead they ensure it’s a continuous process, always feeding back using Citizen Space. This allows for an open conversation between residents and the local authority, validating that their voices were heard in the process.

Arnstein’s Ladder of participation would argue that these actions are performative and don’t provide citizens with real power. While this may have been true in 1960s America, the world has changed and consultations now form an essential part of the overall decision-making process, with citizens views carefully considered and taken into account.

As long as there is legitimate citizen participation, Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation forms a base model to jump off, and nothing more.